Understanding the Basics of COVID-19, Acute and Chronic Illness

Although COVID-19 is a complex viral illness, understanding the basics of infection, acute illness, and its subsequent chronic outcomes can help inform future research, patient care, and prevention strategies.

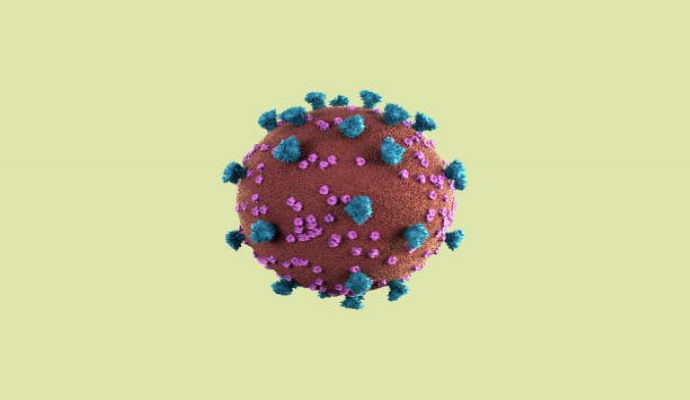

Source: Getty Images

- The COVID-19 pandemic has been one of the past decade's most significant global public health crises. Originating overseas and beginning in December 2019, this viral illness has had an unparalleled global reach, straining public health systems worldwide and infecting millions. While the disease is ever-evolving and the research is being updated daily, understanding the basics of COVID-19, from infection to acute and chronic illness, is critical to better equip providers and public health professionals for future research, prevention strategies, and patient care.

SARS-CoV-2

COVID-19 — sometimes referred to as coronavirus or just COVID — is a viral illness that originates from an infection by the SARS-CoV-2 viral pathogen.

The first discovery of this pathogen was in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. In August 2022, Science published a study analyzing disease spread, noting that numerous cases originated in a market in Wuhan, notably parts of the market areas selling live animals.

SARS-CoV-2 is a part of the coronavirus family, a class of viruses that cause many common colds, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). While many infections by this class of viruses are common, some, including SARS-CoV-2, can be severe and life-threatening.

Researchers in Science also concluded that the pandemic originated from a zoonotic jump from a host animal to humans at the market, causing the disease to spread. According to the CDC, this virus is spread between humans through respiratory droplets projected from the mouth or nose. On a molecular level, the spike proteins on the surface of the virus attach to human cells, allowing the virus to replicate and spread.

Since its initial discovery, the virus has spread rapidly, infecting millions of people and resulting in the ongoing COVID pandemic. Scientists and healthcare workers have learned more about this viral infection — and as the virus has mutated — they have discovered that this disease, which was once thought of as a simple acute respiratory illness, has more widespread and persistent impacts.

Variants

As the pandemic has progressed, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has evolved, with new variants emerging. The CDC notes, “As genetic changes to the virus happen over time, the SARS-CoV-2 virus begins to form genetic lineages. Just as a family has a family tree, the SARS-CoV-2 virus can be similarly mapped out. Sometimes branches of that tree have different attributes that change how fast the virus spreads, the severity of illness it causes, or the effectiveness of treatments against it. Scientists call the viruses with these changes ‘variants.’ They are still SARS-CoV-2 but may act differently.”

Acute Illness

SARS-CoV-2 typically has a 2–14 day incubation period — although average incubation periods may be different depending on the variant — before patients begin to present with symptoms; however, the severity of the symptoms can vary dramatically between patients. In general, symptoms may include fever, chills, cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, body aches, headache, loss of taste or smell, congestion, runny nose, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and other flu-like symptoms.

The NIH divides acute infection into five categories: asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, and critical illness. The severity of symptoms, pulse oximetry, and imaging are used to assess the overall severity of the infection.

Asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic individuals have no symptoms or don’t yet have symptoms but have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 through a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or an antigen test. This state of illness can be perilous as patients are still infectious. Asymptomatic patients who do not get tested or are not isolated, as indicated by CDC guidelines, will exacerbate disease spread.

Mild illness refers to any common signs or symptoms of COVID, excluding shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal imaging. Patients who are moderately ill will have symptoms, a lower respiratory disease confirmed by a clinical assessment or imaging, and an oxygen saturation lower than 95%.

Severely ill patients will have an oxygen saturation below 94%, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to a fraction of inspired oxygen less than 300 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of greater than 30 breaths per minute, or lung infiltrates greater than 50%. Finally, critical illnesses include respiratory failure, septic shock, and organ dysfunction.

Despite the critical importance of pulse oximetry, some things could be improved. According to a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 2022, pulse oximetry accuracy varies based on race. Black patients are more likely to have pulse oximetry readings higher than their actual blood hemoglobin saturation. This implies that Black patients are less likely to be classified as having a more severe illness despite having equal or lower oxygenation levels.

Long-COVID

In addition to the acute symptoms caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, data has shown that many patients also experience persistent symptoms or other long-term complications after the initial infection. With limited data on the long-term impacts of COVID-19, providers need more insight into how to manage or minimize these outcomes.

Post-COVID conditions may be referred to as long COVID, post-acute COVID-19, post-COVID sequelae, and more. The varying nomenclature of this condition is appropriate, considering its variable presentations. In a report published by the CDC in December 2022, the organization noted that 3,544 deaths since the start of the pandemic had been related to long-COVID.

Defining Long-COVID

The CDC notes, “Although standardized case definitions are still being developed, in the broadest sense, post-COVID conditions can be considered a lack of return to a usual state of health following acute COVID-19 illness. Post-COVID conditions might also include the development of new or recurrent symptoms or unmasking of a pre-existing condition that occurs after the symptoms of acute COVID-19 illness have resolved.”

Despite many patients recovering 4–12 weeks after acute infection, the CDC defines post-COVID conditions as being unrecovered 4 weeks after the acute phase. The organization also notes that, while the presentation may vary, it will typically include persistent symptoms that began at the time of acute infection, new symptoms after a patient has started to experience some relief, an evolution of symptoms, or worsened pre-existing conditions.

Persistent Symptoms

One of the most common manifestations of long-COVID is persistent symptoms, meaning that the signs of the acute infection, such as cough or loss of taste, continue or return after the acute infection. While statistics on persistent symptoms vary dramatically, the NIH notes that many sources believe that infected individuals who have completed their primary vaccination series are less likely to experience post-COVID persistent symptoms.

The CDC notes that SARS-CoV-2 impacts nearly every bodily system, including but not limited to the cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurologic, endocrine, and psychiatric systems.

Respiratory and Cardiovascular Issues

An article written by experts at Johns Hopkins Medicine notes that symptoms of long-COVID may include permanent respiratory issues such as shortness of breath, a byproduct of scarring from the infection. COVID may also contribute to pneumonia, bronchitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and sepsis.

According to a study published in JAMA Network in August 2022, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 were at higher risk of venous thromboembolism, such as pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis, than those hospitalized for influenza.

Additionally, COVID-19 may leave many patients with lingering heart problems. According to an article published in JAMA, COVID-19 may cause cardiovascular complications, including but not limited to abnormal heart rhythms, inflammation, blood clot, stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

Research on the cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19 determined that the spike protein on the virus’s surface can damage heart muscle by causing inflammation.

“Host natural immunity is the first line of defense against pathogen invasion, and heart muscle cells have their own natural immune machinery. Activation of the body’s immune response is essential for fighting against virus infection; however, this may also impair heart muscle cell function and even lead to cell death and heart failure,” said Zhiqiang Lin, PhD, assistant professor at the Masonic Medical Research Institute, in an AHA press release.

Neurological and Psychiatric Issues

According to an interview with Allison Navis, MD, published by Mount Sinai, neurological COVID-19 symptoms may include cognitive issues, headaches, paresthesia, neuropathic pain, dysautonomia, and fatigue.

The mental health impacts of long-COVID are complex; however, understanding them is critical to providing comprehensive patient care. As previously mentioned, long-COVID may be associated with cognitive issues. In a 2022 study from the University of Cambridge, researchers found that approximately 69% of patients reported brain fog. Additionally, 68% reported forgetfulness, and 60% had aphasia, causing difficulty collecting the right words. Overall, these mental health symptoms have significantly impacted a patient's quality of life after acute COVID, causing nearly 75% of study participants with severe symptoms to be unable to work.

A study published in the Lancet Psychiatry determined that mood and anxiety disorders resulting from COVID infection were likely to resolve within two years of infection, explaining that rates of these psychiatric side effects did not differ significantly from other respiratory diseases.

Conversely, other psychiatric and neurological outcomes, such as the risk of psychotic disorder, cognitive deficit, dementia, epilepsy, and seizures, could be more permanent after COVID-19 infection.

Other Concerns

Furthermore, long-COVID may affect many other bodily symptoms and contribute to unfavorable, long-term health outcomes. Many studies suggest that a SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy can alter a baby’s neurodevelopmental outcomes. According to the NIH, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults and children (MIS-A and MIS-C) is a common complication of long COVID. Additional long-COVID symptoms may include the development of endocrine disorders such as diabetes.

Best Practices

While sources have yet to pinpoint definitive ways to prevent or treat long-COVID, many organizations, including the CDC, have proposed best practices for healthcare providers.

The CDC has multiple recommendations on how to assess and test for long-COVID. The primary way to determine long-covid is to conduct a physical examination, including blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygenation, and body temperature. Additionally, providers may conduct testing to confirm post-COVID conditions. While laboratory testing will not definitively confirm long-COVID, it may help rule out other conditions or pinpoint the exact impact of infection.

Regardless of how the condition is diagnosed, the CDC advises providers that effective long-COVID care should include the following:

- holistic management depending on the patient's lifestyle

- trauma-informed approaches to symptom assessment

- informing patients and their families of the varying presentations of long-COVID

- continued follow-up care

- collaborative efforts by care teams, including specialty providers

- connections to social services when necessary